Bugbee's Bridge

I grew up in the 1960’s and 70’s on the “Sondreal Place”, located exactly two dirt roads and one optional highway stop sign east of Finley, North Dakota, where our family made up the entire population (6) of that particular section of land. It was called the “Sondreal Place” because at some point a family with that name lived there, though no one could remember exactly when that had been. But once a place had a name, it never changed, since “GPS” at the time consisted of someone telling you (based on landmarks) where to turn and in what direction. With such oral directions being so critical in everyone getting where they needed to be, the landmark names could not be changed without some sort of meeting. And such meetings were rarely held, since neither the organizer nor the guest list could be ascertained, and no one likes meetings anyway.

This farm was an ideal place to be me. I didn’t just love it; we were one. To the north and west of the house were shelterbelts of ash, cottonwood, and crabapple, with a patch of large willow trees near the slough nestled between. To the east was a large area of wetlands that attracted ducks, geese, muskrat, coot, mink, raccoons, and more. By the time I was 15 I knew every inch of the farm and the features of the land for a couple of miles in all directions; I could identify dozens of animals by their tracks and therefore knew where each ranged during which seasons. The same went for the flora. For hunting season, I knew which potholes would usually hold enough water for ducks to gather, and for trapping season, which held the most muskrat, where the mink spent their hunting time, and where the fox trails were.

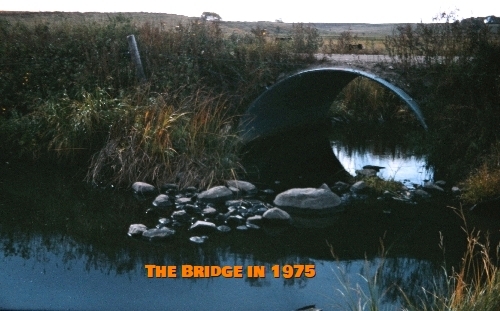

Within that radius, I discovered Bugbee’s Bridge when I was around ten years old. It was called that because the nearest farm was owned by a family named Bugbee. The bridge no more belonged to them than it did to any of the sheep they raised, but again, primitive GPS ruled the day. About a mile and half to the north of the “Sondreal Place”, at the bottom of a broad but shallow valley of tall grass, scattered shrubs, small trees and incredible beauty, the bridge provided a way to cross one of the many tentacles of the Goose river watershed that meanders through. A gravel road that today warns of being “minimum maintenance”, passes over what is at that point a very small stream. As you approach the bridge from the south, you are on flat land until you pass by the Bugbee farm (of which little evidence still remains) at which point the road jogs left as it descends the valley (to avoid one of the tight turns in the stream) then back to its original course as prescribed in the Northwest

Ordinance. For quite a few years, sheep grazed in the valley, keeping large areas of the pasture trimmed down like the greens at Augusta.

Of course this crossing of the river is not so much a bridge as a large culvert; a corrugated steel half-pipe, probably 6 feet or so high. The water that passes through from west to east lands on a small erosion-preventing peninsula of various sized glacial rocks and boulders, which make an excellent access point for fishing or just observing the quiet pool of water (probably around 30 feet across) that juts out into the pasture. Just to the west of the bridge, springs can be found at the base of an outcropping of rock, which were placed there to ensure that there will always be water flowing under Bugbee’s Bridge, and that the gurgling flow out of this pool can always be heard by those that stop long enough to listen.

After my first encounter, I somehow convinced Dad we should try fishing there. We quickly found that the fish were either unfamiliar with this human activity or there wasn’t much to eat, as they would try to swallow the bobber, the sinker and even a bare shiny hook. And they were always biting. As a ten-year-old, the creek chubs we caught were “trout”, and in my father’s quiet wisdom, he never corrected me. Eventually I grew older and more curious, and even without the internet, got the species correct. In fact, the combination of Bugbee’s Bridge and the stream it interrupted proved to be a teacher of whatever lesson you were willing to learn. For example, I eventually would use that pool for catching minnows to go fishing in “real” lakes. I found that the minnow traps I built would catch minnows indeed, but also crayfish. Further observation revealed that if you leave the traps untended, you end up with all crayfish and lots of minnow skeletons.

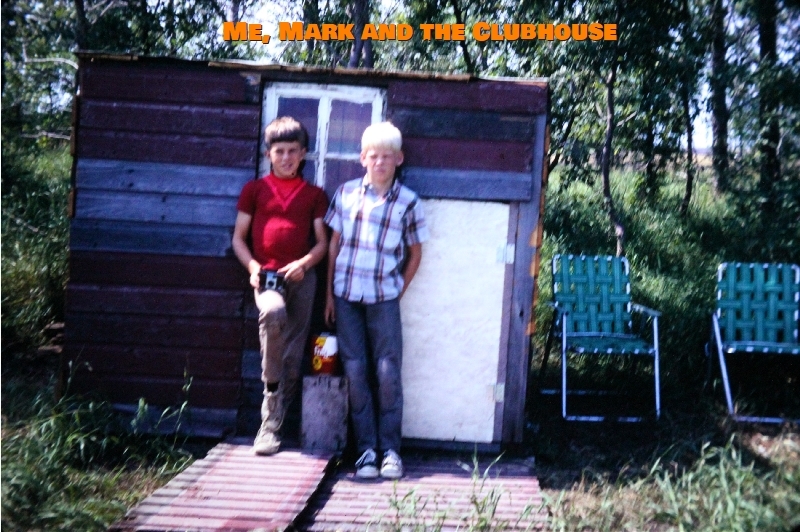

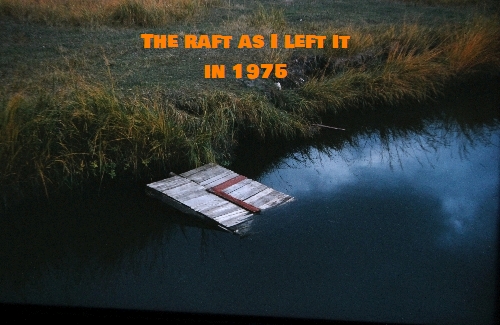

My best friend Mark and I spent many a summer day at the bridge. When we were around twelve years old we organized a club whose charter only allowed the membership of he and I, and, using lumber from tearing down an outbuilding on a neighbor’s farm, built a clubhouse complete with a flat roof that kept everything out but the rain. Sitting at the bridge one day fishing, our discussions turned to the life of mariners. We did have a lot of lumber left over from the clubhouse project, so naturally we started discussing watercraft design and the dream of sailing across … the thirty feet or so to the other side of the pool. Ironically as adults we would both become engineers, but at that point we were all dream and no slide rule. We figured formulas involving water displacement and buoyancy and mass were redundant. We reasoned: “we have wood; wood floats; let’s make a raft”. So we constructed a raft using the only design in our repertoire; a studded

wall. How proud we were when we dragged the 8-foot square wall over the fence to the pool, christened it and slipped it over the bank into the water. It floated! Fishing pole in hand, I eagerly stepped aboard, which of course instantly stood the other end up in the air like the final moments of the Titanic, in the process depositing me and the fishing pole in the abyss. Fortunately the abyss was only 3 feet deep, and I climbed back on shore, deeply disappointed in what was obviously the utter failure of the laws of physics. Back to the drawing board we went.

Mark was more well-traveled than I was and had once seen something called a pontoon boat. He described one to me, and I instantly knew what we should do with all those empty 5-gallon steel oil cans back at the farm. We strapped 6 of them to the bottom of the raft, and we were in business! As we sat on our craft, dreams and schemes were hatched about all the places we would visit. Grand Forks! Winnipeg! Could we make it across the border? We eventually decided we just as well go all the way to the Hudson Bay! What an adventure we would have! A dream deferred.

Now the Bugbee family that owned the farm included a daughter that was about our age. On one particularly hot summer afternoon, Mark and I were on the opposite bank of the pool, fishing and discussing our future Twins’ baseball careers (as a lefty, he would play first base, I would be the shortstop), when she rode up on her bike. I can’t recall how the conversation started, but it eventually came to a challenge to us to swim across to her with the promise of a can of pop for each of us. Now if I had been sitting there by myself, we would have had a good laugh and that would have ended it. But one of the best things about Mark was (and is) his willingness to always embrace new adventure, so he looked at me and said, “let’s go”. The next thing I knew we were kicking across the pond in our jeans and tennis shoes. It only took 15 seconds, but when we got there she was laughing hysterically in disbelief. After that day, we started going in the water every time we had the chance (eventually leading to another lesson, this one in how to remove leaches from your legs).

My last summer in North Dakota was 1975, celebrating my 16th birthday in that year in August. On one of those perfectly northern midsummer mornings, I awoke for no reason around 4:30 and went to the window that looked out to the north, over the slough and shelterbelt trees, and opened it all the way. (Each window in our standard cubical-shaped 19th century farmhouse was unique in size and shape and had a storm window for winter and a screen for summer. We held a twice-yearly ritual that involved finding the matching numbers and rotating to screen for summer and storms for winter.) This window had no screen on it that year so it could be used by a rifleman to pick off gophers that were ravaging the lawn on that side of the house. Thus, I was allowed an unfettered panoramic view of that spectacular predawn moment in time. As a teen, it had not “dawned” on me how really early it

gets light at that latitude, and I was mesmerized.

Some weeks before, the circumstances that would require our family to move that fall or winter had come together, and the plans were already in motion. I was beyond devastated, and in that moment at the window, I was wishing the world and time would just freeze, with the family asleep and together in an awesome place at an absolutely perfect instant in time, the predawn world in which we lived showing me a glimpse of heaven. But the sun came up that day as it will tomorrow, and Dad started his new job in Las Vegas, NV in October. The rest of us followed with the full move in January, after a fall that I filled with as much life as I could. There were dances, a football season of practices, Friday night lights, and game-saving tackle heroics; my last duck and goose hunts with my high school buddies; mink, muskrat, and fox trap lines with Mark, and of course the last visits to Bugbee’s Bridge.

On a frigid day in January, the moving truck pulled in the yard and we packed out the house and left North Dakota, the only home I had ever known. Thus abruptly ended my childhood. Our new home was on a cul-de-sac about a mile from Fremont street in Las Vegas, and as much as I felt the “Sondreal Place” was where I could be me, this tiny place in a sea of concrete, cars, and endless houses was nameless, leaving me utterly lost with no GPS in sight.

Despite all that has been written warning that you cannot go home again, from the first moment I was made aware of the move, I was planning how I would get back to North Dakota. Saving every penny I could, after high school I did indeed make it back and got a degree at the University of North Dakota.Thus I was able to spend quite a bit of time in my old hometown, which eased the shock of leaving the first time. I live in Minnesota now, so I make it back periodically to visit my old home ground, and I always go past the “minimum maintenance” road sign to visit Bugbee’s Bridge. It remains remarkably unchanged. The raft is gone (probably got tired of waiting and went to Hudson Bay without us), but the pool and rocks remain. As promised, the water is still flowing exactly as it did those decades ago when I first discovered it, and likely will still be flowing long after I am gone. Frozen not in time, but in eternity, and that brings me peace.

By the way, if you are out there, you know who you are. Mark and I are still waiting for those drinks.